Stories From Our Ancestors - The New Jersey Fighting Fifteenth

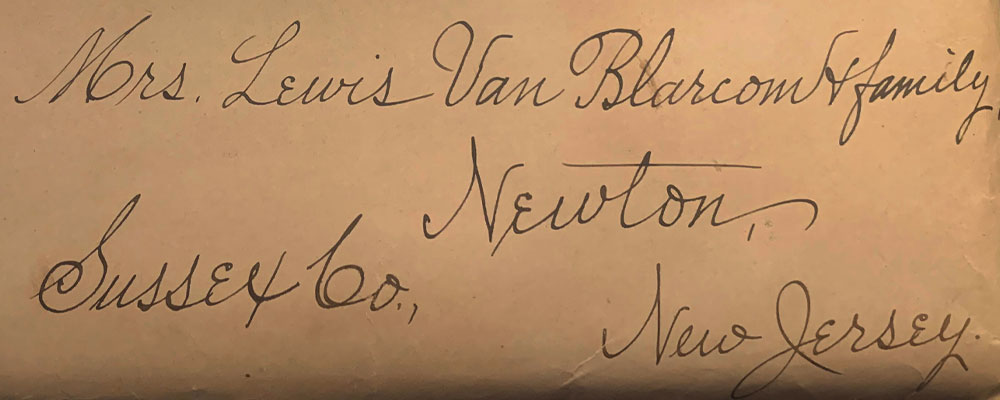

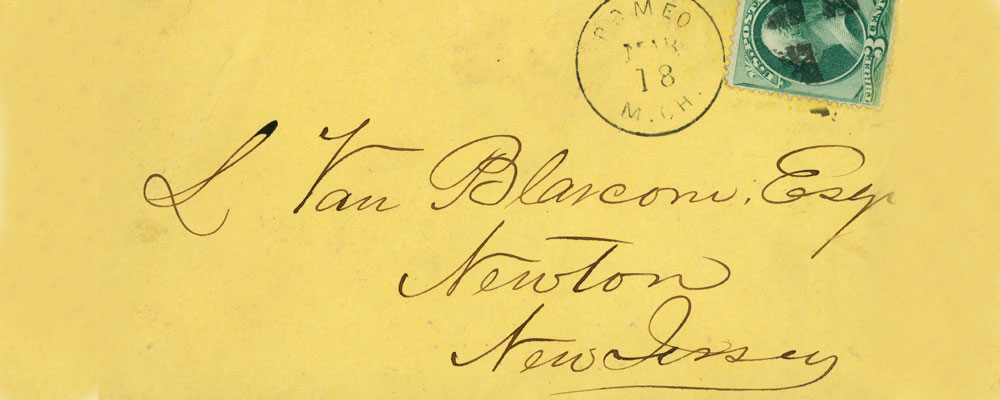

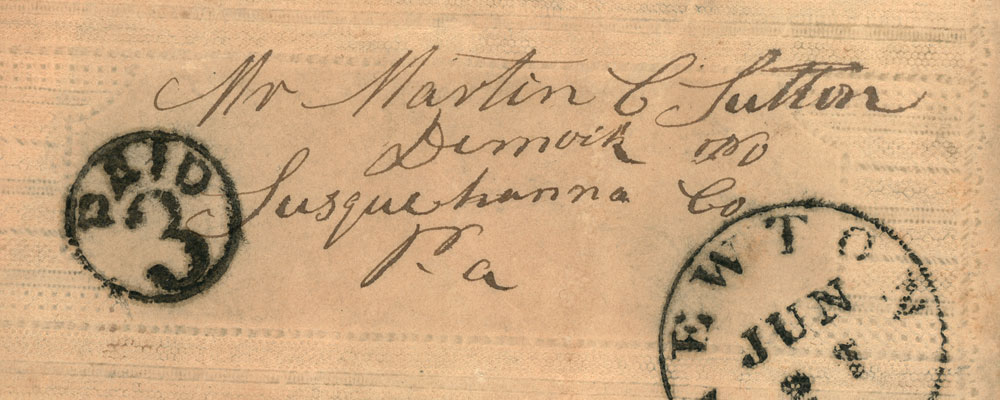

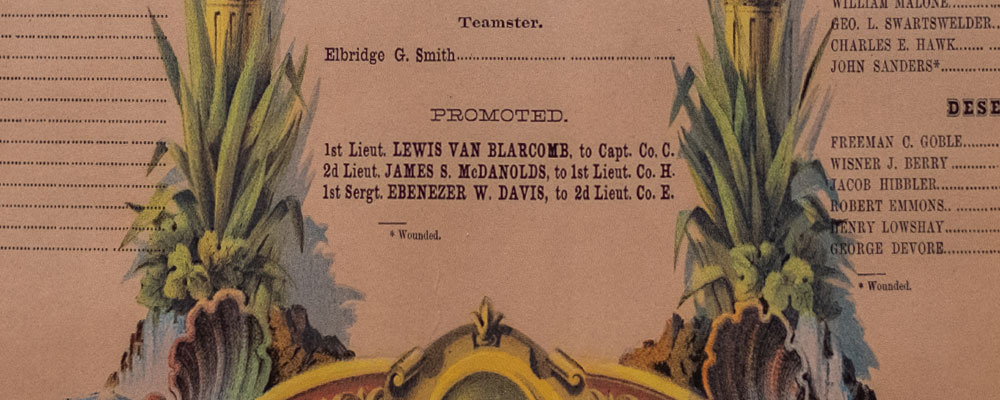

One of the most rewarding aspects of my family research has been finding stories, photos, and artifacts that help me recreate what life may have been like way back when. I have been lucky in some cases that some family members carried a bit of prominence—nothing like the celebrity of today—but enough so that some of their stories have lived on. One story in particular is a narrative by Lewis Van Blarcom, Captain of Company C, 15th New Jersey Volunteers. The New Jersey "Fighting Fifteenth" saw action in many major conflicts of the Civil War. Lewis's story of his last days in the war was published in "The History of the Fifteenth Regiment New Jersey Volunteers" by Alanson A. Haines, who was Chaplain of the Regiment. Below is his narrative in full from the Haines book.

The photo above is of the line officers from that regiment, from the John Kuhl Collection. Front Row, left to right: Captain Cornelius C. Shimer, Company A; Captain William T. Cornish, Company H; Captain James Walker, Company D; Captain Lewis Van Blarcom, Company C; Captain Ellis Hamilton, Company F. Back Row, left to right: First Lieutenant Lowe Emerson, Quartermaster; Captain James S. McDanolds, Company B; Lieutenant James Northrup, Second New Jersey Infantry; First Lieutenant Ebenezer Davis, Company I; First Lieutenant William J. Cooke, Quartermaster, Fourth New Jersey Infantry; First Lieutenant William Van Voy, Company C; Sutler Samuel Young; First Lieutenant Nehemiah Tunis, Company B; First Lieutenant John P. Crater, Company E; First Lieutenant Edmund D. Halsey, Adjutant; First Lieutenant William W. Penrose, Company F.

NARRATIVE OF CAPTAIN LEWIS VAN BLARCOM

The series of conflicts known as the battle of Spottsylvania commenced on Sunday afternoon, May 8th. 1864. The first division of the Sixth Corps was pushed ahead, and in the absence of General Sedgwick, on that Sunday afternoon, was under the orders of General Warren, commanding the Fifth Corps. We reached the rebel position about noon; were first formed in line of battle in an open field, and then marched to the left and filed into a wood almost at right angles to our first position. In front of us, across an open space about one hundred yards in width, upon a wooded eminence, the rebels were apparently posted, proved by the dangerous frequency of rifle bullets from that direction. Just before sundown General Warren rode up in full uniform and stopped at a short distance from where I was and inquired, "Where is the commander of this regiment?" Col. Penrose responded, "I am." Warren then said, "I ordered this brigade into action an hour ago. Colonel, form your brigade and charge; I want to develop that hill." In five minutes we were in motion. Upon emerging from the wood we encountered a sharp skirmish fire, which was kept up during our advance across the open space, with little effect, however. Upon reaching the top of the hill we found the rebels in strong position about a hundred feet from its verge, behind hastily constructed works composed of earth and logs. They opened on us with disastrous effect, firing by ranks. At the second discharge I fell, my left leg shattered above the knee with a rifle bullet. I turned, crawled back over the edge of the hill to get out of the line of fire. When I stopped I saw our men just entering the wood from which we charged, took out my knife, cut my pantaloons where the bullet had struck me to learn whether I was bleeding or not, as I had a tourniquet in my pocket, found there was no bleeding. Shortly a rebel appeared behind a bush a few feet above me and called out, "You are an officer, surrender." I said. "My leg is broken; go back and get some men and carry me off." In a few minutes four men appeared with a stretcher and called out to me to crawl along the side of the hill behind some bushes near by, as where I lay was in sight of our sharpshooters. Dragged myself to the place indicated, was placed upon the stretcher and carried to the rear of the rebel line. Found the position occupied by the Eighth South Carolina, Colonel Hennigan commanding, of McLaw's division. As I lay upon the stretcher the rebels gathered about me, and a lieutenant inquired where I was hurt, and remarked that as I would probably have no further use for my sword he would like to have it. I said, "certainly," and unclasped the belt and handed it to him. He coolly unbuckled his old straps, threw down his sabre and buckled mine on. The blade was a fine one, that my company had presented me but a short time before. A moment after, as I lay upon the stretcher, a little fellow came up to me and said, "Haven't you got something to give me?" I handed him a book, which he received with thanks, and I told him if he would get my cap which fell from my head when I fell, I would give him my watch. He started off and in a few minutes returned with it, and the exchange was made. I lay there all night under a pine tree. Colonel Hennigan treated me very kindly; furnished me with two blankets, and directed me to command his orderly in case I wanted anything through the night, his tent being near by. The next morning I was carried to the rear a couple of miles, to the field hospital of the division, located in a planter's yard. Four surgeons were in attendance. They gave me the option to direct amputation or resection. The oldest surgeon present said, "Young man, we will do as you say, but you had better have that leg taken off. We can perform a resection, but your leg will be shortened four inches; will not be as useful to you as an artificial leg, and you will have only about one chance in ten to live." I decided upon amputation. Lay in that yard under some boards near a fence, with, in my judgment, skillful surgical attendance, with a man specially detailed to wait upon me, until the 19th. On Thursday, the 12th, there was much commotion about; in the afternoon batteries were planted on the eminences, and the next morning a surgeon told me that that point had been selected as a new line of resistance; that a little more pressure would have broken their lines in the great battle of the day before. On the 19th I was placed in a big wagon and carried, much of the distance over corduroy roads, to Guiney's Station, and there put in a box car and taken to Richmond, arriving there on Sunday morning, May 22d. I was placed in an ambulance and the driver directed to go to Libby Prison. I remember the bells were ringing as we passed through the streets, and people were on their way to church. After riding some time I asked the driver—a little darkey—"how near we were there?" He said he did not know. I told him he had better inquire. He stopped and called to a passer-by, "Can you tell me where the Liberty Hospital is?" Though the situation was not very comfortable I could not resist being amused at the little darkey's mistake. However, we were rightly directed and soon arrived at the place. I knew it by the little sign " Libby & Son," hanging at the door. The ambulance was backed up to the door and I was carried into the prison.

My wound had not been dressed for three days, and I was in such an exhausted state that I hardly raised my head until the morning of the Wednesday following. Then felt much stronger, and looking around I encountered a familiar face not over ten feet distant, in the person of Colonel Ed. Cook. He looked at me carelessly and turned away; I said: " Ed., don't you know me?" He sprang up, and called out in a voice that could be heard all over the ward: " Lew. Van Blarcom, you look as though you had been sick three months." The Colonel remained in the ward about a week, and I ascribe my improvement from that hour much to his encouraging and vivacious talk. He told me all about his capture in the Dahlgren raid, and how he came to be in the hospital department of the prison; that a few mornings before he had told the rebel surgeon, a Dr. Franklin, that he was sick; that the doctor grunted out, the best thing he could prescribe for him would be a rope; that he responded, he would prefer a ham. It turned out that Cook had the measles, and hence his transfer to the hospital. I remained in the prison till the 12th of September following. There were on the average about one hundred wounded officers in the ward. Scarcely a morning came that from one to five were not carried out dead. I lay next the wall near a window. There were six beds in that row, and during the time four officers died thereon. The surgical attendance was good, and the attendants were our men brought front Belle Isle. The rations were dealt out but once per day, consisting of a piece of corn bread, two inches by three, about an inch thick, a spoonful of brown sugar, half a pint of buttermilk, and the same amount of black pea—soup, with an occasional suggestion of meat in it. The vegetable, called pea, was a cross between the bean and the pea, infested with insects in all stages of development, from the maggot to the fly. We would skim off the maggots, and, if a few whole peas remained after eating the soup, and the head of a fly protruded from any of them, we would remove it, being careful to save the pea. Occasionally we would have two or three small tomatoes or potatoes. Bread and potatoes could be bought by those who had the money. A four—ounce loaf of bread at one dollar Confederate money. I sold my overcoat and vest for eight dollars Confederate money, and bought eight of such loaves of bread. Some of the attendants had money; how obtained we did not inquire; most probably taken from the bodies of the dead. Lieutenant Horn, who occupied a bed next to mine, conceived the idea of borrowing money from attendants, which we did, on the basis of giving our note for one dollar, for two dollars Confederate money. One George Dehoof, if living, now holds my note for over thirty dollars borrowed in that way. I remember a Massachusetts lieutenant sold his gold watch for nine hundred dollars, and invested twenty dollars of it in the purchase of a water—melon, on which a few of us had a rare treat. Our time was occupied much the same daily, smoking, talking and reading. Reading matter was furnished in abundance—newspapers, books and pamphlets. I am much indebted to Colonels Fairlamb and Bennett, both Pennsylvanians, for entertainment and instruction. They were gentlemen of culture and large information. Mr. Bocock, Ex—Speaker of the House of Representatives before the war, frequently visited the prison, and held long and animated discussions with Colonel Fairlamb upon the war, its causes, etc. The notorious Dick Turner visited the prison daily as a sort of inspector. He was not at all as black as painted; was the best dressed man in Richmond, so said, and always bore himself toward us like a gentleman. General Ould, lately deceased, then commissary of prisoners on the Confederate side, often visited the prison.

Religious services were held every Sunday, usually by captured Chaplains of our own regiments. For a few Sundays the exercises were conducted by Dr. McCabe, reported to have come from Baltimore. He was evidently a man of much ability, but could not repress his secession proclivities. On the last Sunday he preached he took occasion to commend the action of the Southern people in precipitating the war. On the instant no further attention was given to his discourse, and a greater part of his audience began talking among themselves. That was the last we saw of Dr. McCabe. After the Presidential nominations there was much discussion among us concerning the political situation. Though mostly Republicans, we were solid McClellan men, and solely for the selfish reason that we did not approve the policy of the Administration on the question of the exchange and parole of prisoners. At that time General B. F. Butler was the Federal Commissary of prisoners, and General Ould the Confederate. We fully understood that the Confederates were willing to exchange on parole, and that General Butler refused, for the alleged reason that the Confederate Government would not regard the conditions of the parole, and would get able—bodied men to increase their ranks, and the Federals would get diseased, half—starved men in return. That consideration weighed but little with us, and we held the Administration responsible for our continued imprisonment. However, in September arrangements to parole were agreed upon; we were released, and, doubtless, all forgot the above—mentioned grievance, and voted for Lincoln. I signed my parole on the morning of the 12th day of September, 1864, and though described therein as Captain, Company "A," One Hundred and Fifteenth New Jersey, made no objection to the little mistake, yet quite well assured that New Jersey had not contributed one hundred and fifteen regiments to the war. It was worth some privation to experience my feelings of exaltation when, on crutches, I went out of the door through which I had been carried over four months before, and was placed in an ambulance in waiting. Driving along Carey street, said, in time of peace, to be among the busiest streets in Richmond, I noticed grass growing among the paving stones. At the landing called "Roelsett's," near the Tredagar Works, we were transferred to an old steamboat, called the "Allison," and soon were steaming down the river. The boat hauled up to what was called neutral ground, near the Dutch Gap Canal. I managed, with the aid of a stout deck hand, to get on the leading ambulance. At that point the river makes a wide detour, the distance being sixteen miles around, and only a short distance—as I remember, about a mile—across. We were driven across, where we found the steamer New York—a large and well—appointed boat—which 'we boarded— An hour after, we were called on the upper deck, and found a table with ample room for all, loaded with sandwiches and other good things. We arranged ourselves around it; scarcely a word was said, but a good deal of eating was done—being the first square meal we had had for months. Soon the steamer was under way. Colonels Fairlamb, Bennett, and myself sat upon deck while the boat was steaming down the river, enjoying the mild September air, especially enjoyable after the prison atmosphere we had endured so long. The second morning after, landed at Annapolis.

The first person I saw on landing, was Sergeant Cline, of Company "A." I had received no tidings from the regiment since I was shot, and learned from him of the death of Captain Walker, Captain Shimer, Lieutenant Van Voy, and the great losses that the regiment had sustained. The next morning went to Washington, and from there home. Though nearly twenty years have elapsed since the events above narrated happened, they are as fresh in my mind as of yesterday, and seem more like the recital of a dream than a reality.